Not only was this week a sad one for the world with the worst attack on America’s soil in its history; it became somewhat sadder for me as my brother Bill gave his life to cancer earlier today. He had been ill for a couple years and struggled valiantly against the disease that relentlessly pursued him. In the end there were just too many attacks on his body for him to fight all at once.

I planned my workday yesterday so that I could visit him; he lives about an hour away in Rumford. Previously, I had made stops in Lewiston, South Paris, Bethel, Dixfield, and Rumford, all on the work-related business. I reached his house a little after 3:00 p.m.

I was glad to see his daughter Jen’s car in the driveway as I approached; she had served well as an excellent barometer of his day-to-day ability to see family members. His son Ryan’s pickup truck was there too; so he was surrounded by his family.

I walked in the door without knocking and sought out Jen. She informed me that Bill was up and doing quite well. I went down the few steps to the room that had become of the center of his social life during the last few months. Ryan was there on the couch with his Dad, engaged in conversation. Bill greeted me warmly and offered his hand. I grasped his right hand and Ryan’s left simultaneously. “See how cold it is,” Bill asked. “Yes, it is,” I said. “Want me to warm them?” I took both his hands in mine and held them until they warmed a bit. I told him that his cold hands reminded me of a woman I knew whose hands were always cold from being damaged from repetitive stress syndrome. They too would warm to the touch, only to lose their heat again when released.

Bill said that he could only be on his feet twenty minutes a day or so because they hurt so much. I asked him how he was doing with all that was going on with him. He pointed to his feet, his stomach and his back and looked very sad, saying that there was just too much for him to fight now. His eyes brimmed over momentarily with tears, desperately hoping against hope that somehow he be helped to beat his cancer. This look quickly passed as he regained sense of what he was dealing with. “But I’m dealing with it,” he said bravely. “I have to.”

We talked about the World Trade Center disaster. He said that he had seen the United Airlines hit the second tower in real time. He had trouble adjusting to what he had seen and said that it was the most dramatic event he’d ever witnessed.

We talked about the future of terrorism and how calling up the reserve might affect Jen. We agreed that if we wore a younger man’s clothes, we would both enlist in the armed services. Soon Jen and Ryan left us alone and he asked me about my job, which was going very well. He was very glad to hear that I was enjoying it.

We talked a bit about our ancestors, but he cut off the talk as too much for him just now. He couldn’t absorb the information I was giving him and this bothered him. He voiced his frustration loudly, creating a long pause in our visit. I asked what we should talk about, and he didn’t have an answer except to say that he thought he would rest. I said that if he was going to rest, then I would leave. He made it clear he wasn’t asking me to leave. I understood that but said that I would go anyway as I had other stops to make before I went home.

I got up from my chair, walked towards his recliner and asked if he would accept a hug. He said that he would. Remembering his cold hands and their telltale message about the ability of his heart and circulatory system to function much longer, I had a vague feeling that this might be the last time I would see him. As we hugged, I said, “Thank you for being my brother.” He thanked me for being his brother as well. I told him that I loved him, and he told me that he loved me too.

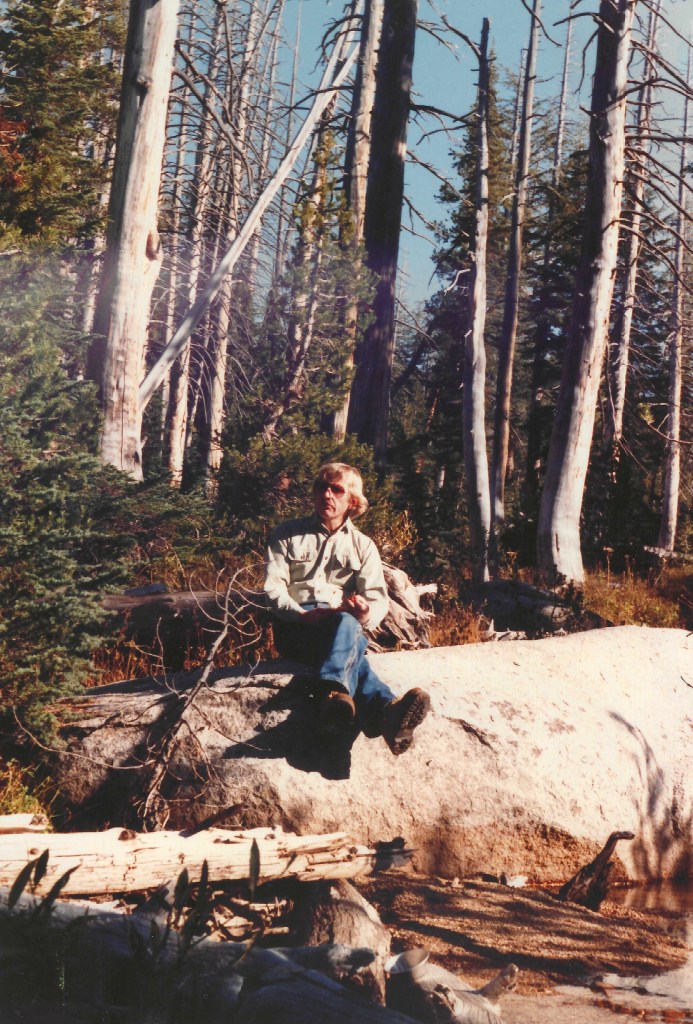

I pulled away to leave. But I wanted to tell him more. I turned and told him that I had thought about the camping trip we had taken to Yosemite National Park in 1984 and how much I enjoyed being with him then. He brightened at this and said that it was the best camping trip of his life. He pointed to collage of pictures on his wall and said that a friend of his thought that the picture I took of him cooking over a campfire was the best camping picture he’d ever seen.

I walked over to look at it and marveled at how perfectly the evening campfire was shaped in the picture in which Bill was wearing a Civil War cap and black and white checked camping shirt.

We were spending the night off the trail because he’d gotten us lost. Not lost, really, just off the trail. He was leading the hike and when he pointed out to me that we were no longer on the trail, I was surprised and concerned. Well, he was an expert woodsman and wasn’t a bit worried. Lacking his skills and self-confidence, I didn’t share his assertion that he would take some bearings in the morning and be back on the trail in no time.

Because we were deep into bear country, we had packed up all our food and strung it up high from a branch quite a distance from our tent, just the way the park rangers had told us. I hunted several minutes for a tree branch that didn’t slope down. They were very scarce. While I bear-bagged, Bill fueled the fire to a warming blaze by the time I returned.

It got dark and cold early, so we drifted off to sleep in his timberland tent. At least he did; I could only think about the bears, tossing and turning on the hard ground.

As I finally started to doze off, I was awakened by a loud crash and wondered for a while if we were to do battle with a grizzly bear. In spite of the noise, all soon returned to quiet; the bear never appeared. Bill had slept through the whole thing.

We awoke the next morning to find the tent covered with frost. After a hasty breakfast, we set out in search of the trail, using Bill’s compass to guide us. Shortly his navigating skills were proven sound as we intersected the well-worn trail to Cloud’s Rest, just north of Half Dome. Shortly, we came across a large old tree trunk that had fallen across the trail, shattering as it landed. This was the Big Bang I had heard during the night; it turned out to be about a half mile from where we had pitched our tent.

We were now at the summit of Cloud’s Rest, the end of our climb. Bill explored the summit, marveling at nature’s ability to create endless beauty and grandeur. We looked down the face of Half Dome, awed by its sheer surface and the forces that created it.

As we began our descent towards the trailhead near Tenaya Lake, We both realized that we had experienced together what neither of us would have undertaken alone. Bill always appreciated the beauty of this hike. He scarcely remembered getting us lost because in his mind, we weren’t. He simply hadn’t taken the time to get us unlost yet. Years later, he did remember all the food I had packed for us and often wondered why I carried food for a week on an overnight camping trip.

Several years later, I hiked with a mutual friend of ours in Grafton Notch and relayed to her our Yosemite trip and my brother Bill getting us lost. She let out a whoop and exclaimed that she too had hiked with Bill and several others, and he had gotten them lost too.

They didn’t have to spend the night lost, but because he had neglected to take into account the return to Eastern Standard Time that day, they hiked by flashlight onto a remote road in a mountain pass. Only Bill was unconcerned. He told me during our final visit that he felt sheepish for the timing error but there was little doubt in his mind that no one was ever lost. Maybe they thought so; but he didn’t.

This hike, by the way, was over a mountain behind Head’s camp in Gilead and was trailless. During our last minutes together, he remembered the woman and almost to his dying breath, was still bothered by her constant doubt about being lost.

I left him, feeling somewhat sad but oh so very glad that I had visited him. Death is unpredictable. He hadn’t intended to die just then. Indeed, just a few moments earlier, he had meted his time for the weekend by having Jen recite the list of prepared meals she had laid out for him for the next day or so.

Several hours later, he was dead. Death just decided that now was the time.

“Because I could not stop for death, he kindly stopped for me.”

By Peter Stowell

September 15, 2001

Related Links:

William R. Stowell Memorial Site on Instagram

William R. Stowell Graduated Third Honors from Gould Academy in Bethel, Maine (1962)

William R. Stowell Graduated from the University of Maine Orono with a Bachelor of Science Degree in Civil Engineering (1968)

William R. Stowell Designed Railroad Crossing on Nuclear Carrying Rail for Mare Island Naval Shipyard, Vallejo, California (1985)

William “Billy” Stowell Playing Guitar with a Local Band on Mollyockett Day in Bethel, Maine – Video by Mike Stowell (1991)